Gabriel Reygondeau was four years old when his father took him fishing off the coast of Mexico. His father and his friends hooked a swordfish and reeled it in, pulling it onto the boat and beating it with a club. While the adults celebrated their momentous catch, young Gabriel stood back, traumatized over what he was seeing. “That swordfish died in front of me,” he said. “At that point, I said I would do anything in my power to work for the ocean and preserve the ocean. You can ask my parents, that’s exactly what I’ve done.”

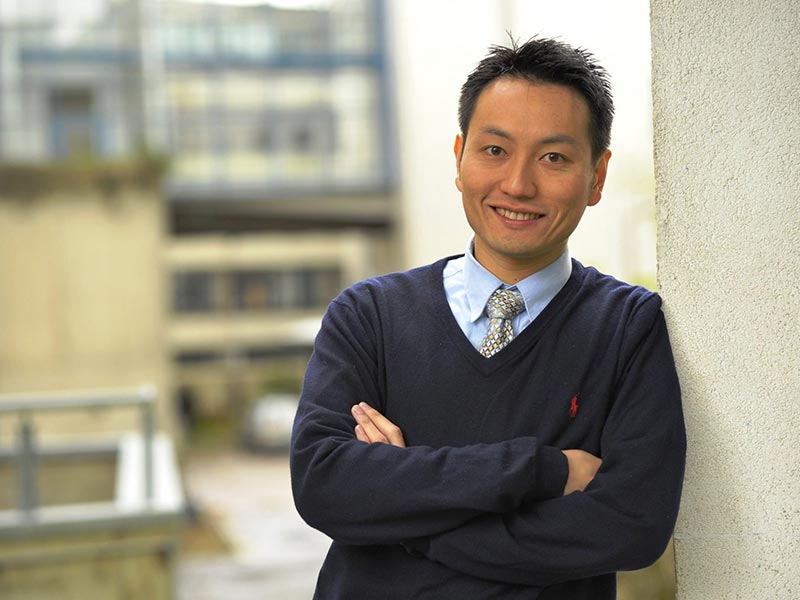

Reygondeau, 40, has been fulfilling that vow ever since, studying oceanography and mathematics as a student, and conducting groundbreaking research that has advanced our understanding of marine biodiversity on a global scale. Now, Reygondeau is bringing that work to the University of Miami, where he was hired as a joint appointment between the Frost Institute for Data Science and Computing (IDSC) and the Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science.

Reygondeau, 40, has been fulfilling that vow ever since, studying oceanography and mathematics as a student, and conducting groundbreaking research that has advanced our understanding of marine biodiversity on a global scale. Now, Reygondeau is bringing that work to the University of Miami, where he was hired as a joint appointment between the Frost Institute for Data Science and Computing (IDSC) and the Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science.

The core of his research is a series of computational models he’s developed to attempt the unimaginable: to estimate the location of every marine species in the world’s oceans and predict where they are moving as climate change alters their environment. Scientists have long tried to estimate fish populations in tiny pockets of the world, usually tied to fishing or preservation interests. Reygondeau is trying to not only combine, but improve, those models to reach a level of detail and accuracy never seen before.

“The complexity of this problem is monumental,” said IDSC Deputy Director Ben Kirtman. “To develop these models, he needs high-resolution data of ocean physics and bio-geo-chemistry. He then uses complex data science and connectivity models so he can predict the distribution of marine species around the world. Gabriel’s efforts in this regard are groundbreaking and setting the scientific agenda.”

Reaching that point has been a true adventure for Reygondeau from the start. His parents worked for Club Med™, the travel operator that specializes in all-inclusive resorts. They moved locations every three to six months, meaning Reygondeau lived in more than 25 different countries by the time he was 15. In some places, there would be an international school he’d attend for a semester, but mostly he was taught by a French tutor that his parents hired to care for him and educate him.

Along the way, he became a regular in windsurfing competitions and even competed as a professional snowboarder for a short time. But as he approached college age, his family finally settled down in Annecy, a mountain village in the French Alps, and Reygondeau knew he needed to get serious about his goal of saving the ocean.

He first attended the University of Savoy Mont Blanc in Chambéry, France, where he received his bachelor’s in ecology and biology. He studied under a professor who specialized in statistical modeling, and Reygondeau realized that those numbers came naturally to him. “That pushed me into stats,” he said.

He first attended the University of Savoy Mont Blanc in Chambéry, France, where he received his bachelor’s in ecology and biology. He studied under a professor who specialized in statistical modeling, and Reygondeau realized that those numbers came naturally to him. “That pushed me into stats,” he said.

He was then selected for a master’s program in oceanography and marine ecology at the University of Paris (also known as the Sorbonne). During his first year in 2006, he attended a talk in Paris by former U.S. Vice President Al Gore as he was promoting his new documentary: “An Inconvenient Truth.” Reygondeau was fascinated by the way in which the film merged climate change—which at the time was considered by the general public to be an upcoming theoretical field of study—with mathematics, turning the abstract into reality.

“That’s exactly the moment I was in Paris doing stats, doing modelling, learning about climate change, and I had access to the people he was talking about.”

“That’s exactly the moment I was in Paris doing stats, doing modelling, learning about climate change, and I had access to the people he was talking about,” Reygondeau recalled.

That revelation led him to Gregory Beaugrand, PhD, a world-renowned oceanographer who became a mentor for Reygondeau and shaped the way he built statistical models. After receiving his master’s (finishing first in his specialty), he was selected for a PhD program at the University of Montpellier and completed the dissertation that would put him on the map: “Impact of climate change on the biogeography of ecosystems of the global ocean.”

For the next few years, Reygondeau made it his mission to seek out and learn from the greatest minds working on biological modeling. That led him to the University of British Columbia in Canada to work with William Cheung, PhD, the leader of the UBC Changing Ocean Research Unit (CORU) and a world-renowned climate and fisheries scientist. Cheung wanted access to the methodologies Reygondeau had been developing, and Reygondeau wanted to learn the math behind Cheung’s models predicting fish movements and exploitation.

Reygondeau also spent time learning about terrestrial biodiversity modelling at the University of Copenhagen and Yale University. In a way, that work is easier because land creatures can be tracked visually, and their movements are largely confined to two dimensions. “You cannot follow a fish,” he said. “We’re playing with three dimensions.” But there was much to learn from the models those terrestrial researchers had built. The end result has been a series of “ensemble models” he’s developed that take the best of all the models he studied. “I don’t think any model is right,” he said. “The truth is in the middle of all these models. I’m searching for the agreement, the average between these techniques.”

The models Reygondeau has built have already helped the World Bank, government agencies, preservation organizations, and others make key decisions about what regions of their waters to protect and how much fishing to allow in each. His models can show a country that a certain species of fish is going to migrate away from it, or that another species is on its way.

Much of that work is already on display on AquaMaps.org, a website that he is co-coordinator of, and FishBase.org, an online encyclopedia of fish maintained by an international consortium of marine ecologists that tracks over 35,000 different marine species. But Reygondeau wants to elevate those models to a new level, and that’s what led him to the University of Miami.

The first lure to UM was having access to the Pegasus and TRITON supercomputers managed by IDSC. He needs to calculate the distribution of more than 40,000 marine species through 2100 according to multiple climate scenarios using up to a dozen different models, so, “I need a supercomputer,” he said with a laugh. But he was also drawn to UM by the prospect of working with Kirtman, the IDSC deputy director whose atmospheric and oceanographic climate models are used by governments and researchers worldwide. Just as Reygondeau was able to improve his oceanographic biodiversity models by studying terrestrial biodiversity models, he wants to link his models with Kirtman’s to improve their output. “Ben is providing me with the physics and the oceanography, and I’m giving him the ecology,” he said.

![]()

The end result, he said, will be a revolutionary website able to accurately visualize marine species at a resolution of 8-10 kilometers squared, a giant leap from current models that have a resolution of 50 kilometers squared. Reygondeau has started a new lab called “AquaX” to do that work as he eases into his new role as associate professor teaching his unique brand of science.

In the meantime, Reygondeau is settling into his new city. He’s living in Coconut Grove and preparing his apartment for the arrival of his family. He’s found a new sport to fill the little free time he has: ultramarathons. And true to his nature, he’s already calculated that running up the Rickenbacker Causeway 340 times is the equivalent of running to the top of Mount Everest.

“That’s doable,” he said. “You can do that in two consecutive days, or over two weeks, because I also have work to do.”

Author: Alan R. Gomez

Read Next: AquaX Laboratory Opens With the Next Generation of AquaMaps.org