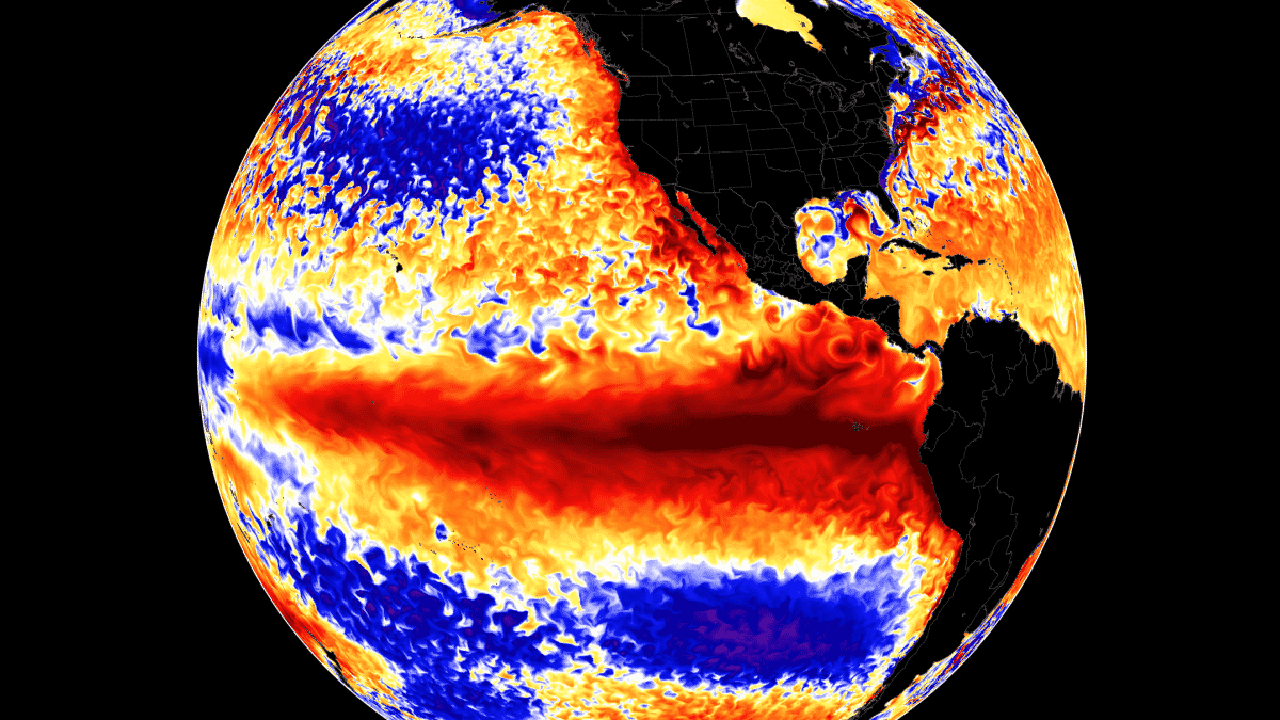

When Ben Kirtman started researching the meteorological phenomenon known as “El Niño” in 1993, few knew what it was and even fewer foresaw what that research could lead to. Now, 30 years later, Kirtman and an ever-growing team of collaborators have not only helped make El Niño a household name, but they’re starting to use the lessons they’ve learned along the way to better understand climate-caused dangers like wildfires in California and coastal flooding along the East Coast of the United States.

“Everything is connected.

In my mind, it’s all one thing.”

Kirtman, Deputy Director of the Institute for Data Science and Computing (IDSC) at the University of Miami, recently secured three grants totaling more than $3 million that will help drive that research. The results, Kirtman said, can influence how governments prepare for disasters, help firefighters prepare for wildfire season, and have profound effects on the day-to-day lives of people living in the shadows of fires and floods. “Everything is connected,” Kirtman said. “In my mind, it’s all one thing.”

Kirtman, Deputy Director of the Institute for Data Science and Computing (IDSC) at the University of Miami, recently secured three grants totaling more than $3 million that will help drive that research. The results, Kirtman said, can influence how governments prepare for disasters, help firefighters prepare for wildfire season, and have profound effects on the day-to-day lives of people living in the shadows of fires and floods. “Everything is connected,” Kirtman said. “In my mind, it’s all one thing.”

Kirtman is most excited that the new projects were driven by his current and former students. In fact, former students are his co-principal investigators on two of the new projects. After spending decades focusing on theoretical and predictive research, Kirtman’s students have pushed him to conduct more practical meteorological research that can improve current-day weather forecasts, and save lives in the process. “People I’m working with really want to do things that matter,” he said. “I want to keep the theoretical and prediction work going because it fascinates me, but translate that to something that helps the world. My students really care, my post-docs really care, so I want to support that.”

Wildfire Season Forecasts

One of the grants will try to improve forecasts that first responders in California rely on to prepare for and respond to wildfires. The state has been engulfed by fires for years, with more than 7,000 wildfires burning more than 331,000 acres and killing nine people in 2022, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. First responders have been relying mostly on generic, short-term weather forecasts and basic prediction tools like the Hot Dry Windy Index (HDWI) that are erratic and can predict weather conditions for up to only two weeks.

Kirtman and Samantha Kramer, one his former students at UM who’s now an air quality data scientist at Sonoma Technology, Inc. in San Francisco, were awarded $822,456 by the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to improve and extend those forecasts throughout an entire wildfire season. They’ll do so using many of the tools Kirtman has developed to measure El Niño, but will also incorporate a wide range of predictive data like wind, humidity, soil moisture, precipitation, and temperature.

Kirtman and Samantha Kramer, one his former students at UM who’s now an air quality data scientist at Sonoma Technology, Inc. in San Francisco, were awarded $822,456 by the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to improve and extend those forecasts throughout an entire wildfire season. They’ll do so using many of the tools Kirtman has developed to measure El Niño, but will also incorporate a wide range of predictive data like wind, humidity, soil moisture, precipitation, and temperature.

What makes that project unique is that Kirtman and Kramer will meet regularly with federal and state emergency officials to cater the research to their needs. Brian Potter, a research meteorologist at the U.S. Forest Service, is even part of Kirtman’s research team. As opposed to other research projects where the practical tool comes years down the road, Kirtman is hoping that working directly with those first responders will help them conduct their research while simultaneously developing a real-time prediction model.

“This is the co-production of science.”

“The way we think about this is the co-production of science,” Kirtman said. “The use case is going to drive how the science is done. Because if I come up with some important fire weather statistic, the fire community is going to go, ‘What’s that? What am I going to do with that?’ Whereas if they come up with it and we tell them how skillful it is and how we formulated it, they’ll trust it, they’ll use it.”

Coastal Flooding Patterns

Another grant will focus on coastal flooding along the East Coast of the U.S., and there again, El Niño will play a big role. People can easily understand how the Pacific Coast is affected by El Niño (formally known as El Niño–Southern Oscillation, or ENSO) since the weather phenomenon originates deep in the Pacific Ocean. But Kirtman wants to show how El Niño affects global weather patterns so drastically that it directly affects coastal, everyday flooding that occurs in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and Charleston, South Carolina.

“What’s the flood forecast for this coming week?”

The end goal is to provide local communities with detailed, daily, and long-term flood predictions, not just when a hurricane is approaching. “When you watch your weather forecast on TV, things are going to start to evolve,” Kirtman said. “They’re going to talk about not only how hot and humid and chances of rain, they’re going to start talking about ‘What’s the flood forecast for this coming week.’ This is the kind of (research) that will inform that.”

Kirtman was awarded $750,000 by NOAA for that project, which he will conduct with UM researchers Emily Becker, Brian Soden, and Brian McNoldy.

El Niño Predictions

The third research grant Kirtman brings him back to his first love: El Niño. Working with another former student—Sarah Larson, now a climate scientist at North Carolina State University—Kirtman will study two of the remaining unknowns for predicting El Nińo. Researchers are now confident they can predict whether El Niño will be active in the upcoming year, but they still can’t predict the intensity of the phenomenon. To do so, they will study the strength of the buildup of hot waters in the Pacific, known as “preconditioning,” and other global weather patterns that influence El Niño.

The third research grant Kirtman brings him back to his first love: El Niño. Working with another former student—Sarah Larson, now a climate scientist at North Carolina State University—Kirtman will study two of the remaining unknowns for predicting El Nińo. Researchers are now confident they can predict whether El Niño will be active in the upcoming year, but they still can’t predict the intensity of the phenomenon. To do so, they will study the strength of the buildup of hot waters in the Pacific, known as “preconditioning,” and other global weather patterns that influence El Niño.

That research will be conducted with a $1.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation.

Winning all three research grants will advance the scientific community’s understanding of each topic. But for Kirtman, they’re also a clear signal that the team he’s built at IDSC, across different departments at the U, and between collaborators at other institutions, is working.

“We’ve put together a great team,” he said.

Story by Alan Gomez | ARG Media

William R. Middelthon III Endowed Chair Honors Dr. Kirtman

In a ceremony held at the Rosenstiel School in May, Dr. Kirtman was named the inaugural William R. Middelthon III Endowed Chair in Earth Sciences. Joining him for the occasion were Rosenstiel School Dean Roni Avissar (standing) and philanthropist William Middelthon III. Middelthon’s support of the University began in 2010 when he met the late professor Robert Ginsburg, founder of the Rosenstiel School’s Comparative Sedimentology Laboratory, who stressed that funding was essential to advance research. Over the years, Middelthon also developed a strong friendship with Dean Avissar, and a deep appreciation for the School’s ongoing research—particularly as it relates to forecasting of natural disasters—which led him to establish the endowed chair. In addition, Middelthon also offered Broad Key, with its dock and ocean-to-bay access, for use as the Rosenstiel School’s primary field station and has supported various initiatives at the School, including the Aircraft Center for Earth Studies and the Helicopter Observation Platform Fund.

“I am deeply honored to be the first recipient of the Middelthon Endowed Chair,” said Kirtman. “It will allow me to continue my research and teaching in the field of earth sciences and to make a positive impact through my work.”

Tags: Alan Gomez, ational Science Foundation, Ben Kirtman, Brian McNoldy., Brian Potter, Brian Soden, Broad Key, California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, el Niño, Emily Becker, NOAA, Robert Ginsburg, Samantha Kramer, Sarah Larson, U.S. Forest Service, Wildfire Season Forecasts, William R. Middelthon III